Pregnancy Complications

Infant- and Family-Centered Developmental Care

Respiratory Infections

Neonatal Eye Health

Hygiene

Rare Diseases

In this deeply moving interview, former NICU parents Joke and Theo Kamphuis and their daughter Juliëtte—born very preterm in the 1980s—share their powerful story of early separation, resilience, and lifelong impact. They reflect on the emotional toll of limited physical contact, the importance of parental presence in neonatal care, and the need for long-term follow-up for preterm babies. Their experience underscores the urgent message of our "Zero Separation. Together for Better Care" campaign: babies and parents belong together—no matter the circumstances. Don’t miss this heartfelt testimony that advocates for change and inspires compassion in neonatal care worldwide.

Question: Mr. and Mrs. Kamphuis, your daughter Juliëtte was born preterm in the 1980s. What was the situation like in the neonatal unit back then?

Joke Kamphuis:

Our daughter was born in a regional hospital located in the eastern part of the Netherlands, and it was immediately clear that this hospital did not have the specialized expertise or the facilities to keep her alive. It was a matter of life or death.

Theo Kamphuis:

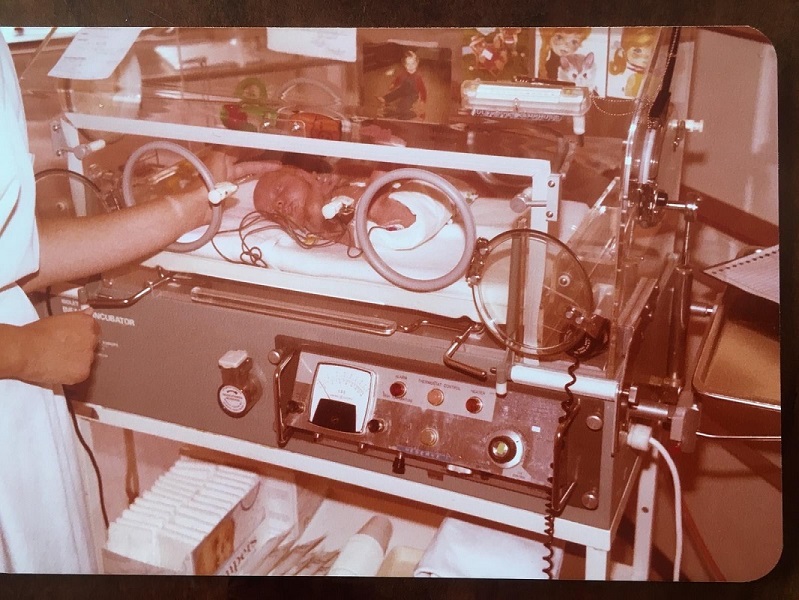

While Joke was recovering from the delivery, the pediatrician-neonatologist spoke to me separately and briefed me on the situation and how we would proceed. It was a clear and honest conversation, and the pediatrician did not conceal how serious it really was. The medical team advised me on how to care for our child, even though they had already taken responsibility and decided to transfer our very preterm daughter to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of an academic hospital.

Meanwhile, the pediatrician-neonatologist called several NICUs across the Netherlands, and it was difficult to find a place for our baby—they were all full. It was very clear to us that if they couldn’t find a place in a NICU, our daughter would likely pass away soon. Fortunately, they found a spot in a NICU in the central part of the Netherlands. Together with the medical team, we made the immediate decision to transfer her to the NICU at this academic center, which was 130 km (about 80 miles) away. I accompanied my baby girl in the ambulance, since there was a risk she might not survive the transport.

During the transport to the NICU, the medical professionals kept me informed about the arrival at the academic center and the next steps for treatment. The transport lasted about 1.5 hours, and the team walked me through various scenarios: “If this happens” or “If that happens” in the coming days, followed by, “As the father, it’s very important for you to know…” They gave me a lot of valuable information, which I deeply appreciated afterward.

Joke Kamphuis:

During the transport, the physician and assistants were constantly focused on our daughter in the incubator and communicated their observations by radio to the NICU at our regional hospital.

Theo Kamphuis:

So, by the time we arrived, the entire medical team was prepared and ready. After a full examination of our baby, the team placed her on a mechanical ventilator and stabilized her.

After the arrival, several hours passed before I saw my daughter again in the incubator. In the meantime, discussions with the medical team continued, and a few photos of our baby girl were taken to later show to Joke. The team asked me questions like, “What should we do if she doesn’t make it?”, “Are you religious?”, “Should she be baptized?”, and “What should her name be?”

From the moment I told them our daughter’s name, they no longer referred to her as “the baby” or “the girl,” but as “Juliëtte.” Suddenly, she became a real human being to everyone involved, and this gave us hope. As a father, I found the conversations with the NICU staff at the academic center extremely valuable. When I returned to the regional hospital, I was able to share my feelings with my wife—and we had the first two photos of Juliëtte to hold onto.

Joke Kamphuis:

This gave us both hope and strength. Without those warm conversations with the medical staff from the beginning, we might have felt less connected—not only to the medical team but also to our daughter. Most of our questions were answered before we even had to ask.

Theo Kamphuis:

The advice of the pediatrician-neonatologist at the regional hospital was also incredibly helpful when Juliëtte was born. His guidance gave us courage and hope. He urged me, as the father, not to leave our newborn alone during the ambulance ride, but to accompany her.

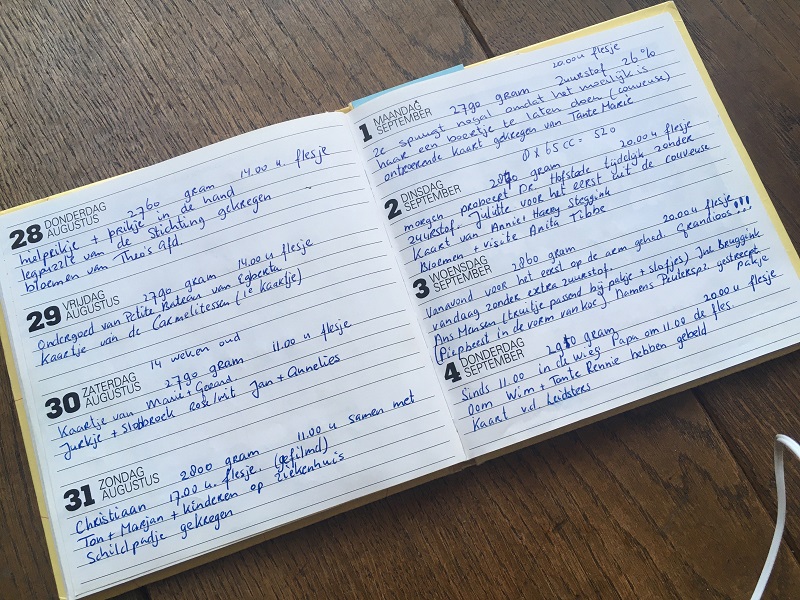

Even at the NICU in the academic center, we were always encouraged to stay in touch by phone or to visit. A photo of our oldest son and some beautiful birth cards from family were placed on the incubator, and the medical staff assured us, “She feels it.” Although it took an agonizing three and a half months before we could hold Juliëtte for the first time, we were encouraged to touch her little fingers or her head. This was incredibly important for us as parents—to be able to touch and connect with her—and for our baby girl, because she could feel that connection.

Joke Kamphuis:

After three months, Juliëtte was transferred from the academic center to a regional hospital near our home, where she stayed for another month. We experienced a big difference in the way we were welcomed as parents. Back at the regional hospital, suddenly nothing was allowed anymore. No physical contact with Juliëtte, for example, and we noticed a major difference in the type of care.

At the academic center, physical contact was a priority—even if it was just touching her, since holding her wasn’t possible at the time. At the regional hospital, this was considered not “medically sterile.” For instance, photos were no longer allowed on the incubator. We felt that fear of contamination should never come at the expense of physical connection between parents and their baby. Babies feel connection through touch.

We, as parents, felt a strong difference in the guidance and support provided by nurses at the academic center compared to those at the regional hospital. This needs to change—especially if such practices still exist today.

We also believe that follow-up care after NICU discharge should be more frequent and long-term for a preterm child. In our case, it was only once a year, with a brief 30-minute interview and a few questions for us as parents. We had expected much more: in-depth evaluations and more comprehensive monitoring of Juliëtte’s health.

The visits were always face-to-face, and after five years, follow-up was suddenly stopped—without any prior discussion or consent from us. We were simply told, “She’s now equal to every other child.” We felt completely abandoned. “What if something happens again?” we wondered.

We were constantly informed about the short- and long-term risks of preterm birth and the possible side effects of the medical procedures that had kept Juliëtte alive. Some of the medications used were quite new at the time, and their long-term effects on preterm infants were unknown. We asked if these could cause health issues later in life. The physician answered, “That could happen to any child.” But in our view, other parents didn’t live in the same fear for the first five years of their child’s life.

Now we know that our daughter developed a chronic lung disease at age 25. So we believe that follow-up for preterm babies should be much longer—if not lifelong.

Question: Mr. and Mrs. Kamphuis, your daughter was born nearly forty years ago. At that time, it was common practice to separate preterm babies from their parents. What impact did this separation have on you as parents, and do you think it still affects your relationship with your daughter today?

Joke and Theo Kamphuis:

Well, that’s a very difficult question to answer. The separation was a medical necessity, but that doesn’t mean we had no access to Juliëtte. We had very intensive contact with the academic hospital, and we were allowed to call as often as we needed. The medical team always made time to speak with us.

Joke Kamphuis:

After nine days of recovery from the delivery, I drove to the NICU at the academic medical center. That was the first time I actually saw my daughter. I always believed that Juliëtte would survive, but I also knew how critical the situation was at the time, and how low the survival rate was. Theo and I are both very down-to-earth, and in the beginning, we put our emotions aside—there simply wasn’t space for them. But that doesn’t mean we didn’t have emotions. We talked a lot with each other about what was happening in the NICU and later on as well. We always managed to reconcile and find a shared path forward.

When I answer this question now, as a mother, my emotions rise up strongly. Maybe it’s because of my age—I’m 71 now.

Our relationship with Juliëtte has always been very positive, and we raised her as a “normal” child, not as a “disabled” child. We did that unconsciously, but now we believe it only made her stronger—both physically and mentally.

Question: What do you think might have been different if you had been able to have more contact with your newborn daughter?

Joke and Theo Kamphuis:

It would definitely have been better for us as parents if we had been able to have more physical contact with Juliëtte. When you can touch your child, it helps you process your overwhelming emotions. But we are both forward-thinking, and we believe that looking back doesn’t help much, because you can’t change the past.

Question: Juliëtte Kamphuis, you were still a baby when you were separated from your parents. Do you think this early separation had any consequences in your life as a child, a teenager, or an adult?

Juliëtte Kamphuis:

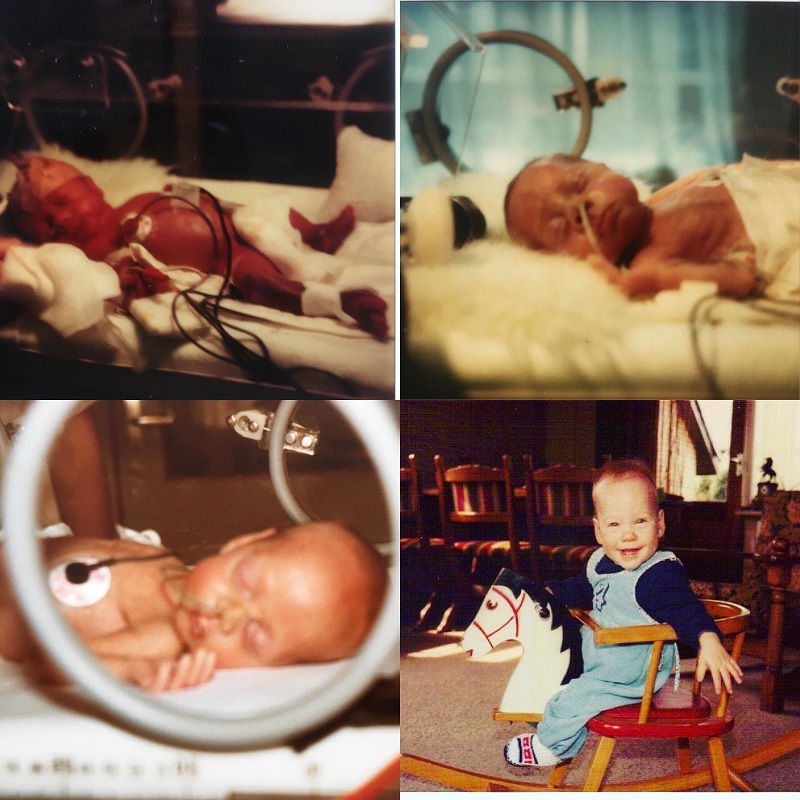

My parents tried to visit me in the NICU as often as they could, although it wasn’t always easy because of the distance, and they also had to take care of my 10-month-old brother. It took a very long time before my mom was finally able to hold me. I was born on May 24, and my mom held me for the first time on September 3.

Maybe it would have helped me as a baby in the NICU if my parents had been able to have more contact with me earlier, such as holding me sooner. It might have comforted me during certain situations—like during painful medical procedures—which I now know must have been hard to endure. It might have also helped me feel less discomfort as a toddler, because I remember experiencing loud environments as very stressful.

I believe this could be related to the noises inside the incubator. An incubator acts like the sound box of a violin or guitar—it amplifies external sounds. Even relatively soft noises from the outside can create strong resonances inside, which may have made me feel distressed.

Still, I believe I must have somehow felt the presence of my parents, especially the strong belief my mother had that I would survive, because I never gave up. I always knew that my parents really wanted me, and that I was loved from the beginning.

Question: Mr. and Mrs. Kamphuis, how do you feel knowing that parents around the world were often not even allowed to see their newborns in neonatal units during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Joke and Theo Kamphuis:

We think that’s awful—it should never happen. For parents, seeing their newborn brings hope and helps them cope during emotionally difficult times. What if the baby dies without the parents ever having seen them? That is extremely traumatic and emotionally unbearable. It’s almost impossible to recover from that.

Theo Kamphuis:

This is exactly why the pediatrician-neonatologist advised me to accompany my daughter to the academic hospital in 1980. He understood how traumatizing it would have been if Juliëtte had died during transport and I hadn’t been there. That’s why we want to emphasize:

There should be no separation at all between parents and their newborns.

Question: Ms. Kamphuis, as a former preterm baby, what do you think needs to change in the current situation?

Juliëtte Kamphuis:

I fully agree with my parents—there should be no separation. Parents must be allowed to visit their newborn baby. It helps both the parents and the baby feel connected through presence and touch. I’m certain that a baby feels this connection, and that it can provide comfort and support during critical health situations.

Medical centers and NICUs should take this into account and ask: What is truly best for the baby and the parents? If babies are unable to connect with their parents, they may later have more difficulty bonding, and may struggle with peer relationships or building emotional connections as they grow up.

And, as my parents said, it’s truly heartbreaking to think that during the COVID-19 pandemic, babies passed away in NICUs without their parents ever seeing them.

It is possible to follow COVID-19 safety measures while still allowing parental presence. Hospitals can adapt the route to the NICU to avoid unnecessary contact with others, parents can wear masks, and they can limit visits to friends or extended family. With the right precautions, connection does not need to be sacrificed.

We sincerely thank Joke, Theo, and Juliëtte Kamphuis for sharing these deeply personal insights, and for their support of the “Zero Separation. Together for Better Care” campaign!

© 2025 GFCNI. All Rights Reserved.